Six years have come and gone since my last “fielding,” and there have been days when I’ve nearly given up.

Backpacking.

Planning for a day when I could return to dreaming.

All of my projects. Everything.

Life changed in ways that crushed whatever plans I’d been making to hike the Appalachian Trail (AT). There would be no grand hike overseas. I had wanted to hike parts of the International Appalachian Trail (IAT), which I was just beginning to learn about. I had corresponded with the co-chair of the IAT about hiking in Newfoundland, but that was before everything changed.

My dad’s death was the first of many passings–shocking because we didn’t know he had cancer until he had a month to live. The larger world mourned the loss of people and plans that we once took for granted as doors closed, funding stopped, and people stayed home.

Every day since then I’ve wondered: will I ever get back to where I was?

Even after the pandemic lifted and I resumed day-hiking on the AT, so much was gone. My job consumed me, my health eroded, and family matters took more of my time.

Years passed, and I took another job. I left East Tennessee and the mountains I still consider my home, and relocated to northwestern Ohio.

The landscape here is flat; far more than the hills of southeastern Ohio where I’d once lived as a grad student. It’s cold in the Midwest. It’s also hot, depending on the season. We have droughts and ice storms and tornado sirens that blast the first Friday of every month at noon. The university is small, but once more, my job takes over, and I teach writing, or call and visit family when I can.

More years pass.

Hiking? Not in a while. Backpacking? Deeper in my past than ever before. I think of deleting this site, but continue to renew every year. Perhaps there’s another project? One that’s greater than the failure I feel now?

Last year I embarked on an exciting adventure. I wrote and produced a novel as a part of an experiment. I wanted to teach my students about this particular area of writing and publishing that I had no experience with. In the process, I found a way to engage with the Appalachian Trail again, and to think of the Earth in a new way. One that would lead me forward into something hopeful from the very dark place that I’d burrowed into.

Perhaps I had been hiding from the fears we face every day: Climate change. War. Natural disasters. Unstable governments and division. Political strife.

But there was a writing contest that drew me in, by encouraging entrants to imagine a better future, even in the midst of climate change. The Imagine 2200 climate fiction contest inspired me to believe in a world that comes after us, that will belong to our descendants, and their children, and the children that come after them. I went back to an old idea I’d had for a novel set over a hundred years into the future. Each year I submitted something to the Imagine 2200 contest, and though I did not win, I kept writing and submitting new stories.

The short stories I wrote became chapters, and in February 2024 I published the sci-fi novel Beyond These Winters under the pseudonym “Liese Jeyd Hartman.” (The ISBN is 979-8218371999 and it is available through your local bookstore as well as Amazon.)

It was out of love for the Earth and in the spirit of creating hope for myself (and others) that I undertook this writing, and now the characters are as real to me as any companion I hiked with on the Trail. In my novel, the landscape of 2149 is altered, but there’s still a continuous walking path stretching north from Georgia to Maine, and beyond, into Canada. In my novel, the Appalachian Trail has become “The Narrow Road.”

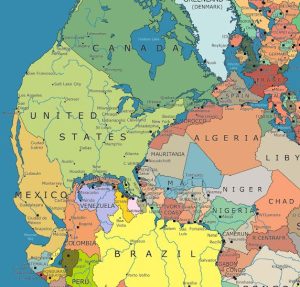

The world of my novel is no less connected, despite the collapse of infrastructure and disasters in North America. There is hardship, and to an outside observer, the “American States” in 2149 may be a dystopia. There are no cell phones, no convenience for those displaced or outside the wealth that has moved steadily north. People have migrated away from the coasts, and the economy has moved toward the Arctic sea lanes which are no longer choked by ice.

And yet?

Humankind persists. People still fall in love. They go on long journeys, and are sometimes motivated by kindness. Whether the story’s setting is a dystopia or a utopia, that may be up to the reader. Much like the lives each of us are living right now, power, wealth, and technology are available to a few, but not all. But by this time, people have learned to manage the threat of human destructiveness through gene editing and nanotechnology.

Utopia? Not after a hundred years of climate change. Dystopia? Depends on where you live, how you live, and how far you or the generation before you has traveled to find a safe haven.

Some things never change.

This is not my last fielding, and not my first, but nonetheless, a new beginning. I’ll keep writing, and the hope is to return to hiking in the coming years and to finish the AT. There’s a little patch of land back home, deep in the forest, and though steep, The Narrow Road runs like the edge of a knife on the ridge above. Landslides gouged the creek in my Momaw’s yard and reshaped the land there in 2021. But the land continues to evolve and so do we all.

Just last year, in late September, a “thousand-year flood” worked its destruction all around that same forest I call home. Hurricanes ravaged Florida, while other parts of the country saw unprecedented rain. It severed hollows from the main road, filled the Nolichucky River to thirty feet above flood stage, took out bridges, homes, people, roads . . . all the rivers of my childhood were pouring through the mountains of Virginia, Northeast Tennessee, and Western North Carolina. I wept to read about cadaver dogs combing the rocks lining these rivers in my home.

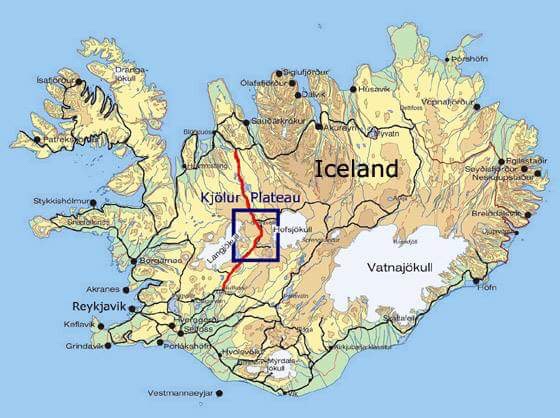

Climate change is all around us, and as I think back to that dream of a hiking project I had in 2019, I realize that the journey is ongoing to understand this Earth and the time that has shaped it. If you need a visual, refer to Ian Webster’s stunning “Ancient Earth” dynamic map. I see where I am now, and it is not too far from my former home in Tennessee when viewed from this distance, 240 million years later.

We are no less connected now than we were before everything changed, and I suspect a hundred years will pass in the same way each century tends to do: painfully, punctuated by wars and disease, fires, flooding, and weather made worse every second, even if we choose to ignore it. How did people live through the twentieth century?

How will we live, in the future?

How does anyone now?

Signing out from the plains north of the Central Pangean Mountains, this thirteenth day of February in 2025