I’ve been concerned about the future of writing instruction ever since Large Language Models (LLMs), usually referred to as Generative AI, hit the public scene in 2023. It wasn’t just the original written works that AI was trained on, but visual art too. The cost to the environment, our clean water supply, the drain on the power grid from the data centers . . . it was all too much. So GenAI became my nemesis at times, even as I intermittently began to find ways to make it useful for my work.

As a teacher of writing, I spent too much time at first trying to police my students’ research papers for academic misconduct.

tl;dr . . . That approach only made everything worse.

That’s why I created Monolith, and–as ironic as this might sound–with the vital assistance of Gemini, Google’s flagship LLM.

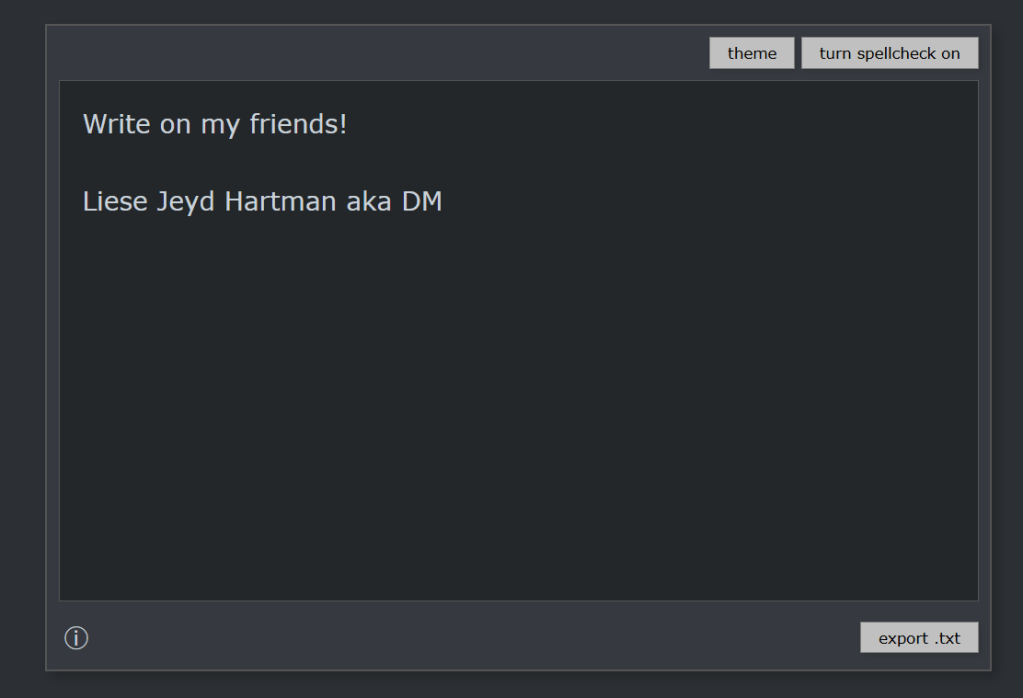

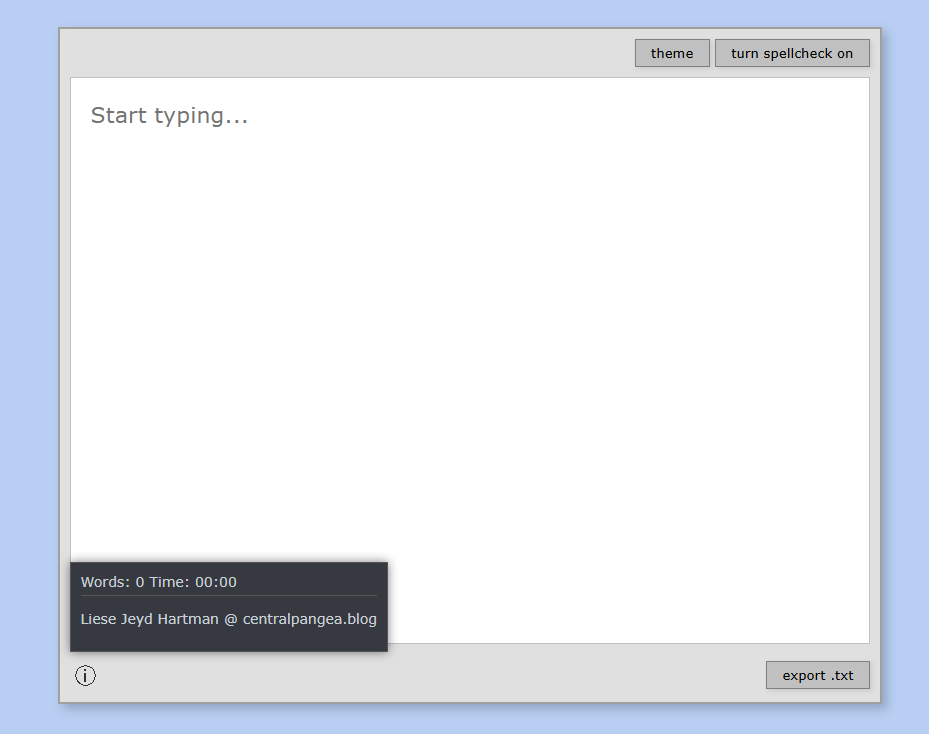

In Monolith, which is intended as a distraction-free writing tool, you can turn the spell check on or off, change the theme (color scheme), and if you hover your cursor over the information button, you’ll see the word count and time for your writing. You cannot copy-paste into or from Monolith, but you can export what you write into a .txt file like Notepad. You can see the default interface below:

If you are interested in the really long version of why I created this writing tool, read on . . .

From 2023 through the beginning of 2025, the harder I tried to fight LLMs and students’ use of them, the more pessimistic and irritable I became. I was especially upset when their creative writing would be flagged as AI-generated.

At first, I took it personally. Then I began to notice that students I trusted, students who loved writing, were being flagged. Maybe it was because they wrote too casually using a general, vanilla vocabulary, or used Grammarly to edit their work. Or maybe I was naive about how integrated AI had become with all of the writing we produce every day.

In the Spring of 2025, I realized that false positives, as well as papers that slipped through AI-detection software, were forcing me to reevaluate my approach to writing instruction.

Over the summer of 2025, I learned that my fully online and asynchronous college writing course was filling with students. The despair set in. What was I going to do?

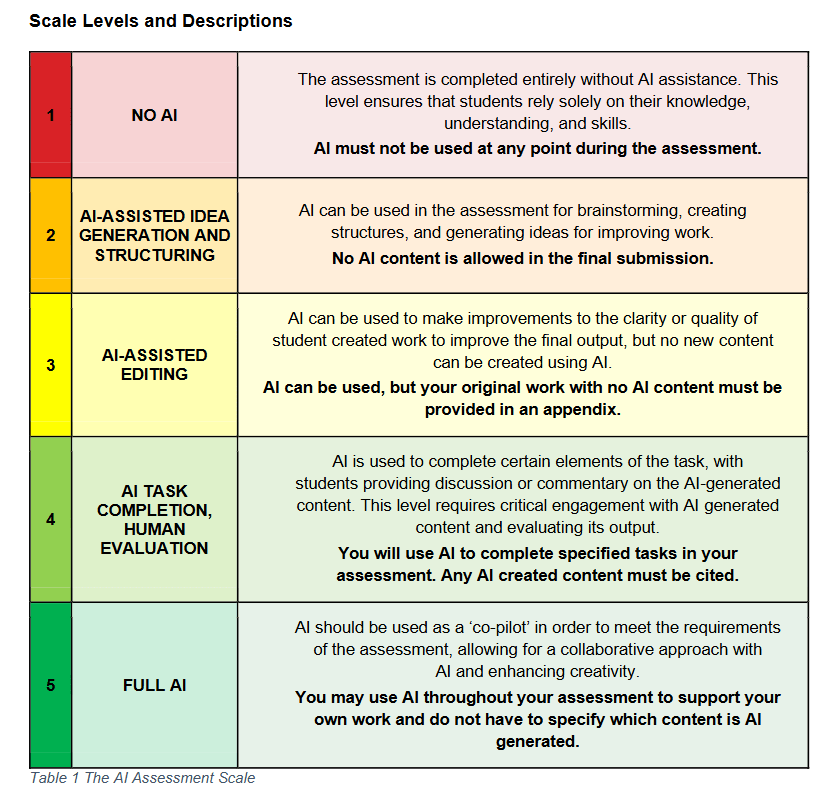

After watching many teaching/learning videos supported by major textbook publishers and reading a number of articles, I decided I would focus on ethical and transparent use of AI in my college writing classes, and ensure that students were aware of the different levels of AI use. This was after I watched Notre Dame’s teaching and learning videos and from there, dove into an article titled “The Artificial Intelligence Assessment Scale (AIAS): A Framework for Ethical Integration of Generative AI in Educational Assessment” by Mike Perkins, Leon Furze, and Jasper Roe, et. al. published in The Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 21:6 (2024). [read it here]

In that article, the writers make a bold claim that:

There is now evidence from empirical research that major academic publishers of scholarly journals do not prohibit the use of GenAI; conversely, many encourage their use to refine and improve manuscripts if their use is declared transparently and if the author takes full responsibility for the accuracy and veracity of the work (Perkins & Roe, 2024). Pragmatically, this seems to be the only option that prepares academics and students for the rapid advances in AI; given that text detection services and combative approaches are flawed (Sadasivan et al., 2023), and a ‘postplagiarism’ world may be on the horizon (Eaton, 2023).

So, I’m not really ready for the “postplagiarism” world just yet, but I was intrigued by the scale of AI-assistance that they present and discuss in this article. Their chart is offered below in Table 1, and explained fully in their article linked above.

Deciding to focus on AI-transparency in my teaching created a new problem, however. What method would I use for ensuring that a student did their own writing initially?

Why, handwriting, of course!

Except, students with dysgraphia and students with serious arm injuries were suddenly at a disadvantage. These are the things that professors learn after they have made a handwritten notebook the cornerstone of their Level 1 (no AI assistance) coursework.

At first, I went back to explore all of the typewriter simulators online. I allowed students to use Freewrite’s Sprinter application, which is a free tool used to market their writing devices. In classrooms, however, the app would regularly glitch, and sometimes students had trouble creating a free account to save their work. As stylish and minimal as Sprinter was, it still wasn’t ideal, and I had specific ideas about what I wanted from my writing tool that would be different from everyone else’s.

At the same time I was deciding to focus on ethical and transparent use of AI in my first-year writing classes, my university followed the pattern of many others in fall 2025. With Ohio State University embracing “AI Fluency,” the new standard was helping students learn better prompting and integration of AI tools into their coursework. My university established a governance policy for our use of AI at work, including the specifically authorized tool “Gemini,” which I had never used before.

As I became more familiar with Gemini, the tool responded beautifully. I was finding new ways to use it so that I could model it for my students when we came to the assignments requiring more deliberate use of GenAI. But I kept coming back to the central problem: how would my students produce that first, free-written draft before polishing it in Gemini?

It was a short step to asking the LLM itself for help. I was trying to figure out what a “GEM” was, and in my curiosity decided I would give it a shot. Could I create a tool that would serve the purpose I needed it to? My first prompt went something like this:

You are a college professor wanting to create a writing application that will be basic, like a text file editor, but does not allow copy paste and does not check spelling or offer predictive text. You would like the tool to be accessed with a link and allow someone to write, have their words counted, and be able to export the file to a .txt file to save on their hard drive. You would like the background to resemble a word processing application from the early 1990s, which is basic and no frills. Typewriter nostalgia and retro styling would make this an awesome app for use in a college classroom for students to take notes in and export their work.

Several hours later, I had viable code. Having worked a little bit with basic .html coding in the early 2000s using Adobe PageMill 3.0, a WYSIWYG program for noobs, I still had to ask dumb questions of Gemini, like: “What is a CSS file?” and “What is Java Script?” Remarkably, the answers that Gemini offered were truly clear and helpful.

Soon I was testing the prototype in a “Code Playground” and looking for ways to host it. By the time I was getting close to what I wanted, I had figured out how to customize the code for colors and button labels, and what each part of the code was used for.

I told a friend about it, also a creative writing professor, and she was thrilled. “You should charge.” I wasn’t confident that what I had created with Gemini’s help had a value, or that I could even charge for something co-written with an LLM. So I said, “maybe I’ll offer a donate button.”

Still working on that . . .

Anyway, that is the story behind “Monolith,” which Gemini suggested the name for. Later I realized that a “monolithic application” is essentially what the writing tool is. Software created for one purpose, and limited in its functionality and scope.

As I said before, in Monolith, you can turn the spell check on or off, change the theme (color scheme), and if you hover your cursor over the information button, you’ll see the word count and time for your writing. You cannot copy-paste into or from Monolith, or drag-and-drop text, but you can export what you write into a .txt file like Notepad.

I welcome feedback from teachers and students about how I can improve Monolith, but for now, please enjoy. There may come a time when I have to pay for the hosting, but for now, I’m happy to offer this as a free beta tool in the search for distraction-free writing experiences.

It may also be a safety for students who are anxious about being accused of using an AI when they didn’t mean to. Perhaps an acceptable accommodation for students who are asked to take essay exams but cannot handwrite them. However you find it useful, please let me know in the comment box at the end of this post.